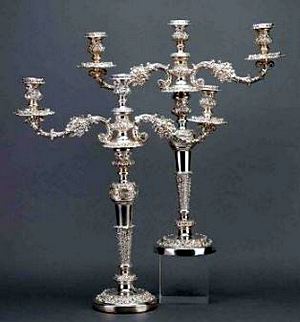

SHEFFIELD SILVER CANDLESTICKS

A certain misapprehension has always surrounded the subject of silver from Sheffield. Popular belief holds that it is the same as Sheffield plate. This belief is justified up to a point, for there certainly was an interlocking of interests between silver from Sheffield and Sheffield plate, as the story of Sheffield candlesticks shows. But silver hallmarked with the Sheffield town mark of a crown is of Sterling standard (see photos), while the "plate" is just that: a thin layer of silver fused onto copper. Sheffield silver marks examples of all types can also be found in our marks4antiques.com on the Internet or other references, such as specialized books.

The story of candlesticks, which were hand-raised from sheet metal until casting became universal during the late-17th century, is one of continuing simplification. The change in method of manufacture was one aspect of simplification of the process. The base (made in one piece) and the columnar stem and candleholder (made in two) were easy to cast. The whole was skillfully joined together, just as the separate parts of the machine-aided candlesticks were joined when that method was perfected later in Sheffield.

There was nothing really new about casting. But the use of the process made things far easier, so much so that candlesticks dating from about the year 1700 survive in large numbers and evolving styles and in good heavy quality that needed no further strengthening.

Evolution, however, did not confine itself to styles. During that century, inventions to reduce both cost and labor followed one another quickly in England's Midlands, easing the supply and demand problem created by a newly affluent society that was not yet really rich. Sheffield plating, a process discovered in 1742, was a boon in more ways than one. It not only simulated silver at a fraction of the cost, but it led to the invention of other processes that were also useful in producing the same type of articles in silver at about a third of the price of the old method. Sheffield silver, in fact, owned a great deal to the fused plate industry since it depended on the same processes. In Sheffield, the two trades worked closely together. Although all Sheffield candlesticks were by no means so insubstantial, most were. This explains why most Sheffield candlesticks had to be loaded with a hard or weighty substance, usually marked as “weighted”. As hollowware, they could not have stood alone. This is also why they were so easily damaged or dented.

NEW STEEL DIES

Candlesticks were being made in Sheffield before the perfection of Die Stamping in the early 1760s. But with the new steel dies, the necessity for hand finishing ceased. The cutting of a die, in reverse, was a skilled job undertaken only by specialists, and many candlesticks required a dozen or more dies, all cut separately. Nevertheless, the effect was most impressive, for not only the shape but every form of decoration stood out clearly on the metal, as if embossed, chased or otherwise worked by hand by a master. This helped in enhancing decorative features and allowed for an increased detail on the finished candlestick. Mass production is hardly the word that would spring to mind, yet once these parts had been soldered together, a strengthening rod inserted, and the hollow filled with pitch or another hardener, the object was complete. This was a much quicker and more efficient method than before.

Before Sheffield was granted its own Assay Office in 1773, silver from that city was sent to London for marking, where the smart trader snapped up candlesticks to resell as London work at London prices, even though those were always cast. This was so lucrative a practice that London silversmiths continued after 1773 and until about 1780 to overstrike Sheffield makers marks with their own. A well-documented example is that of John Carter, known for his fine “London” candlesticks, but we now know that he resorted to this type of trade frequently.

From the start, certain Sheffield firms specialized in candlesticks, including John Winter & Co. who made many graceful sets. This did not prevent other firms from producing very fine sticks in addition to other objects. The whole question of makers, however, is extremely involved. Whereas some partners were concerned solely with sales, many "names" belong to several companies. Confusion for today's collectors is the natural result. The basic construction of candlesticks was also affected. There were firms who, while assembling no sticks themselves, specialized in the production of parts for sale to others, so that the same base, or stem, or nozzle, stamped out by the thousands, might be used by many small makers, each stamping his own punch.

Again, many of Sheffield’s registered silversmiths were Silver platers first and foremost, and it was in the plating industry that the best designers and die cutters were mostly employed. With dies costing up to $150, an extraordinary amount of money for that time, the best use had to be made of them. With silver doubling the possibilities, it became expedient to form a silver company with a silversmith in partnership. Some of the top makers also belonged to several firms of the same standing, so their names appear in many combinations. This naturally also affected the use of dies whose circulation was not confined to one firm and its subsidiaries. Therefore, many of the same dies might be used by several firms and for both Sheffield plate and silver.

DIVERSITY OF DESIGNS

If it were not for the endless possibilities for varying available parts, this would lead to a terrible sameness among Sheffield candlesticks. But when the number of die cutters, firms, designs and parts are considered, this practice still allowed for a huge number of variations of designs and styles to be made. It is true that no one maker's work was distinctively his. Yet it is possible to fail to recognize the similarity instantly from a row of sticks all set on a base from the same die, so different is the effect.

Styles revived every known form, from Gothic through Rococo to Greek Classical motifs. Nevertheless, it was in the Adam period (ca 1760s – 1790s) that Sheffield silversmiths excelled, showing their full powers of original design, aided by the suitability of thin-rolled silver to a style that was so essentially graceful. Other styles could come and go, but Adam candlesticks never ceased to be popular to this day. It was largely these that Victorians and others, using old Sheffield dies, produced as genuine period pieces.

Some pieces are dated, such as many shown in the accompanying photos. Other famous Sheffield silversmiths include John Watson who produced mostly Rococo styled pieces ca 1816 and stamped accordingly. Others are not. Candlesticks, tapersticks and candelabra, which often had plated branches to save expense, were mostly made in the Adam style from an immense range of designs. Decoration on these, whatever their shape, was elegant to say the least. As heavier, more ornate forms came into fashion, designers adapted as needed. What Sheffield candlesticks lacked in weight of silver was well compensated for by the designers.

Chamber sticks, which lost their purpose of lighting people's way to bed during the 19th century, never attracted these designers to the same degree. Very few attempted more than the gadrooned edge and leaf-capped handle, although a few followed the Adam Neoclassical line. Telescopic candlesticks, however, invented in Sheffield and exclusively made there, are another matter. These were of a utilitarian nature and were intended to throw a constant light, height being adjusted as the candle shortened, so avoiding strain on the eyes when reading, sewing, and so forth. Consequently they were seldom made in silver as table sticks were, and still more rarely in a set of four. Most were of Sheffield plate, designed to extend to varying heights. Some were very small, round and plain, and few are decorated beyond rayed flutes, gadrooned or beaded edges.

These were first made in 1790, but in 1798 when Samuel Roberts patented his machine to produce candlesticks that moved effortlessly to any desired position, they reached their zenith and were made for the next 25 years. Telescopic candelabra were simply an extension of these. According to old invoices, candelabra have a history as old as candlesticks, but it was not until Sheffield makers reduced their costs that they became more common. Even then they were more frequently made in plate, almost universally so in the 19th century with the exception of some notable examples by Storr and a few other makers.

In an 1809 example by John Watson, the candleholder and waxpan were stamped out in one piece, often over 20 inches high, and had remarkable decorative detail. Fenton, Allanson & Co. went even further. The weight of the silver branches on one of their pairs alone came to 136 ounces. Fenton, along with Richard Creswick, was one of the original names in Sheffield.

But such pieces are rare and because of this they are often faked or made up, sometimes using the holder of an old stick, particularly the chamber type, which usually displays the silver marks. The one safeguard against this is correct attribution of these silver markings, with every single detachable part at least partly marked at the same time. This, of course, goes for all sticks. One form of faking is to make a cast from an old pair. Old dies may lose a little sharpness with continued use and age and so the fake mold will have lost the sharpness of the marks, appearing very unclear. But, as they say, for Sheffield makers, “copying is the ultimate form of flattery”.

Unlock the true value

of your collection with our comprehensive research guides from identifying makers' marks to appraising all kinds of

antiques and collectibles.

Our up-to-date information will give you an accurate understanding of your items' worth. Don't miss out on this

valuable resource - visit our research tools today!

Search our price guide for your

own treasures